Background: Jewish and Islamic Religious Courts

Jewish and Islamic legal systems, governed by Halacha and Sharia respectively, guide the religious and personal lives of their adherents through courts known as Beth Din (Jewish) and Sharia courts (Islamic). These systems, rooted in sacred texts—the Torah and Talmud for Halacha, the Quran and Hadith for Sharia—address matters like marriage, divorce, and disputes, but differ significantly in their training, authority, and societal acceptance. In places like the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Israel, both systems operate alongside secular law, often for voluntary arbitration, yet their approaches to jurisdiction and influence reflect distinct philosophies. This post argues that Halacha, administered through Beth Din courts, embodies a non-imposing, community-focused legal tradition that respects secular law, while Sharia courts often reflect an imperative to expand Islamic law globally, raising concerns about coercion and universal application.

Halacha: A System of Restraint and Respect

Training and Authority

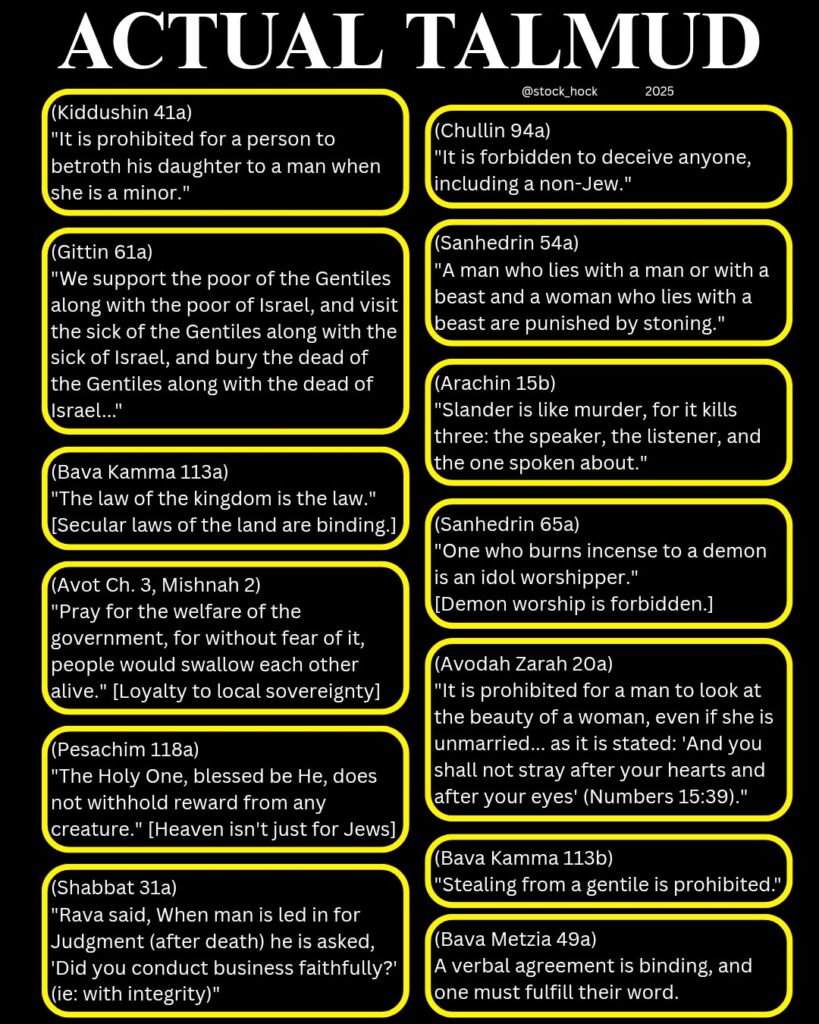

Halacha, meaning “the way” in Hebrew, is derived from the Torah, Talmud, and subsequent rabbinic interpretations, codified in works like the Shulchan Aruch. A Beth Din (house of judgment) typically consists of three rabbinic judges (Dayanim), each requiring extensive training—often 5–10 years—in Jewish texts, legal codes, and ethical principles. This includes mastery of the Talmud’s 63 tractates and practical training under seasoned rabbis to ensure precise rulings. Dayanim are often conversant with the secular law of the land or consult local lawyers to understand legal boundaries, ensuring compliance with civil frameworks. Judges must be observant Jews, often immersing in a mikveh (ritual bath) for spiritual purity and adhering strictly to commandments like Shabbat observance, reflecting their role as moral exemplars. Authority stems from communal acceptance, not coercion; parties must voluntarily agree to the Beth Din’s jurisdiction, and its rulings are unenforceable without secular court approval. The principle of dina d’malchuta dina (“the law of the land is the law”) ensures Halacha respects secular legal systems, limiting its scope to observant Jews and excluding criminal matters, which are left to state courts.

Acceptance and Non-Evangelical Nature

Halacha is not evangelical; it governs only those who choose to live by it, typically observant Jews. Jewish courts do not seek to impose Halacha on non-Jews or non-observant Jews, focusing instead on internal community matters like kosher certification, marriage, and divorce. The Beth Din’s role is advisory for those who opt in, and its rulings, such as those on business disputes, are often submitted to civil courts for enforcement. A significant concern is get refusal, where a husband denies his wife a religious divorce document, leaving her unable to remarry under Halacha. However, Jewish communities often address this through social pressure, public shaming, or sanctions like exclusion from synagogue activities, mitigating the issue’s impact. In modern contexts, civil remedies, such as Section 10A of the UK’s Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, allow courts to delay final divorce decrees until a get is granted, further protecting women. This community-driven approach and deference to secular law underscore Halacha’s non-intrusive nature.

Sharia: A System with Global Aspirations

Training and Authority

Sharia, meaning “the path” in Arabic, is derived from the Quran and Hadith, interpreted through fiqh (jurisprudence) by scholars across various schools (e.g., Hanafi, Maliki). Training for Sharia court judges (qadis) varies widely, with some requiring years of study in Islamic law, while others, especially in less formal settings, may have minimal formal education, relying on basic knowledge of religious texts. Unlike Dayanim, qadis typically do not engage with secular legal systems or consult local lawyers, leading to potential conflicts with civil law, especially in Western contexts. In Muslim-majority countries like Saudi Arabia or Iran, Sharia courts wield significant authority, often enforcing criminal penalties like flogging or amputation, based on strict interpretations. In Western countries, Sharia councils operate as arbitration bodies for family and business disputes, but their authority is limited to consenting parties and subject to secular law. However, significant community coercion often undermines this consent, particularly for women, who may face intense social pressure to submit to Sharia rulings. Reports, such as a 2016 BBC investigation, highlight cases where women felt compelled to accept Sharia council decisions on divorce due to fear of ostracism or worse. In extreme cases, rejecting Sharia arbitration can lead to severe consequences, including “honour killings” or threats for apostasy, as seen in documented incidents in countries like Pakistan and even within some diaspora communities (e.g., the 2007 murder of Aqsa Parvez in Canada). For individuals seeking to avoid Sharia arbitration, the fear of such repercussions may force them to “disappear” or sever ties with their communities to ensure safety. The lack of standardized training and oversight further exacerbates these issues, particularly in matters like divorce, where women may face prejudice due to male-centric interpretations (e.g., talaq, where a husband can unilaterally divorce by pronouncement).

Acceptance and Global Imperative

Unlike Halacha, Sharia carries an imperative for observant Muslims to promote its application universally, rooted in Quranic verses like 9:33, which calls for Islam to “proclaim it over all religion.” This has led to efforts to integrate Sharia into public spheres, such as demands for halal food in schools or workplaces, sometimes resulting in pork bans that affect non-Muslims. In some Muslim-majority countries, Sharia governs all citizens, regardless of faith, imposing rules like dress codes or restrictions on non-Muslims, as seen in Iran’s mandatory veiling laws. In Western nations, advocacy groups have pushed for Sharia-based arbitration to be recognized, raising concerns about coercion, especially for women pressured to accept rulings that may undermine their secular rights. A 2016 BBC investigation noted instances where Muslim communities sought to expand Sharia’s influence through arbitration councils, with women reporting pressure to comply, reflecting broader advocacy for Sharia’s public role, contrasting sharply with Halacha’s limited scope.

My Argument: Halacha’s Ethical Restraint vs. Sharia’s Expansive Ambition

Halacha’s strength lies in its restraint and respect for secular authority, embodied in dina d’malchuta dina. Beth Din courts serve observant Jews who voluntarily seek their guidance, without imposing Halacha on others. The rigorous training of Dayanim—spanning years of textual study, ethical practice, and often familiarity with secular law—ensures consistent, principled rulings, while community mechanisms and civil laws address issues like get refusal, demonstrating adaptability within a non-coercive framework. In contrast, Sharia’s variable training standards, lack of engagement with secular legal systems, and global imperative, as seen in efforts to enforce Islamic law in public spaces or entire nations, can clash with secular values and individual freedoms. The coercive pressures within some Muslim communities, including risks of “honour killings” or punishment for apostasy, further highlight Sharia’s potential to encroach on personal autonomy. For example, in some UK schools, halal meat has become the default, limiting choices for non-Muslims, while Sharia councils’ rulings on divorce can disadvantage women due to less oversight and community coercion.

The Jewish community’s commitment to Halacha is a personal, community-oriented practice that respects the broader society’s laws, never seeking to dominate or convert. The push for Sharia to influence public policy, from dietary restrictions to legal arbitration, reflects a fundamentally different approach, one that observant Muslims may view as a religious duty but which can encroach on others’ freedoms. Policymakers should recognize Halacha’s compatibility with secular governance and protect its practice, while critically examining Sharia’s expansive aims and coercive tendencies to ensure they align with democratic principles.

Conclusion

Halacha, through Beth Din courts, offers a model of religious law that is rigorous, voluntary, and respectful of secular authority, focusing on the Jewish community without evangelical ambitions. Sharia courts, while serving similar functions for Muslims, often reflect a broader goal of universal application, compounded by community coercion and risks like “honour killings” or apostasy punishments, particularly in diverse societies. By understanding these differences, we can better appreciate Halacha’s ethical framework and advocate for policies that support religious freedom without compromising secular values.